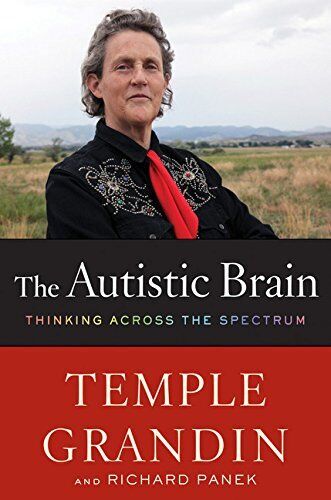

A book review of the ‘The Autistic Brain’ by Temple Grandin and Richard Panek

Temple Grandin is a professor, best-selling author, animal behaviourist, and faculty member with Animal Sciences in the College of Agricultural Sciences at Colorado State University. While Grandin is, at face value, a scientist, there is another aspect of her identity, crucial to understanding the origins of this book. At the age of 12 , Grandin was diagnosed with autism, despite it initially being labelled as brain damage.

Grandin starts by describing her own personal experience of being autistic, particularly in the early stage of her diagnosis, and her traits, for example, inability to speak, destructive behaviours, sensitivity of physical contact, fixation on spinning objects, all traits that now scream autism, but were missed.

Grandin also focuses on the experiences of nonverbal autistic people, a group wildly misunderstood and underestimated. My personal favourites included Tito Rajarshi Mukhopadhyaig and Carly Fleischmann. They both discuss the sensory difficulties they experience during conversations, as well as their experiences with sensory overloads, how when overwhelmed by sensory stimuli, they have what many would describe as ‘temper tantrums’ or the other side of the spectrum, being ‘unresponsive’. Grandin uses this concept of ‘acting self vs thinking self , which essentially describes one’s internal experience compared to one’s external presentation. The frustration of both Fleischmann and Rajarshi Mukhopadhyaig is when your thinking self and acting self don’t match up, and they are found in a situation where one the inside the feel or ‘act’ one way, but struggle to translate it verbally or physically, in other words, their ‘acting self’. This defeats the stereotype that simply because someone is unresponsive or struggling to communicate, in this case verbally, that does not signify lack of intelligence or lack of understanding.

Something I personally found very useful was how at the end of the chapter on Sensory processing disorders, she included techniques of how to cope with sensory overload, some of which I incorporated into my own life. For example the use of deep pressure to help desensitise as well as prioritising sleep as auditory processing problems are worsened by sleep deprivation. I learnt that the hard way after having two hours of sleep, and all it took was someone dropping a fork to send me into a complete overload because the sound just kept echoing around my mind.

I particularly enjoyed the focus on research on autism, which was very interesting given her scientific background. For example, the significance of neuroanatomy in the context of autism, and the way in which one’s brain overdevelops certain regions to compensate for the lack of development of another, a trait typical to autistic brains. The research around the difference in neuroanatomy enables scientists to start attempting to diagnose autism using neuroimaging tools, most notably MRIs. This would be extremely useful, especially when it comes to early diagnosis in young children so that they can access the help available. While the techniques were reasonably accurate, it wasn’t enough for them to be the only thing looked at for a diagnosis. She also explored the hidden gem that is music therapy. I’m sure most people would admit that music can definitely impact one’s state of mind, whether you need a bit of Queen to hype yourself up before a presentation, or some Conan Gray to get you out of bed in the morning, autistic people are no different! Music-based interventions have been ‘underutilised’ in terms of facilitating speech output. A 2005 study analysed data from 40 autistic people who had undergone 2 years of music therapy, and all forty showed improvements in language and communication. So if I’m constantly wearing headphones, now you know why!

My favourite thing about the book was how it deconstructs the stereotypes and assumptions about autism. For example, a few weeks ago, I was watching a film at the cinema with a group of friends, and the main character did something that ended up comprising his team’s efforts, and I heard the person behind me say ‘God he’s so autistic’. At the time that comment made no sense to me, I was confused as to how someone making a dumb decision equated to them being autistic, especially seeing that autistic people tend to have an above average intelligence. But I’ve started to hear it more and more, even at school, which made me realise, there is such a negative connotation around autism, and people have so many assumptions about it that simply aren’t true. The more I’ve spoken to classmates about it, the more I’ve realised that people just do not understand or know what autism really means.

Even among researchers, we have only really scratched the surface of what it really means to be autistic, especially among females who tend to present differently as they tend to ‘mask’ a lot better. This lack of research can make it not only difficult for others to understand you, but also for you to understand yourself, which is why I want to study it at university and beyond.

This book also was of particular interest to me as I am currently in the process of being diagnosed with autism. It’s a relatively new development in my life and it’s a part of my identity I have yet to explore and learn about. I actually cried of happiness at several points in the book, simply of how much relief I felt that other people thought the same way as me, and that there wasn’t anything ‘wrong with me’, and most importantly, I wasn’t alone. I think that’s why books like this are so important, it’s not just about the research, but also the sense of community it provides.

By Annabelle, student